[Editorial] Gone Girls: Missing Women on Screen

The horror genre is full of active, complex female characters that drive narratives and become iconic figures. Far from the perception that women are always victims, reduced to undressing, running and screaming to up the gore and titillation content, horror presents a multiplicity of varied and interesting roles. The nature of the genre means that women are often in danger, resulting in their disappearance or deaths, but this does not necessarily mean that they do not have a significant impact on the rest of the story. For this article, I have selected some female characters from the genre whose disappearances and/or deaths become driving forces for the plot. As plot points will be discussed, here is your warning for spoilers for all the film and television cited, including sequels.

Before the list, I wanted to add an honourable mention for Carolyn Harper, the missing teen from Jennifer Reeder’s Knives and Skin whose disappearance sparks a melancholic and often musical response from the community. As parents and other adults increasingly come undone, the teenagers find unique ways to deal with their grief in a film that divides opinion. As there is no current UK release I could not undertake the kind of detailed re-watch I would normally like to do before writing but the film deserves further attention.

Laura Palmer – Twin Peaks

Sheryl Lee struck such a chord with series creator David Lynch, that he created another role for her in the form of Madeleine (Laura’s cousin) , despite her original character dying before the start of the series. Lee has now played Palmer in television and film since 1990, culminating in The Return (2017) where her cryptic “I’ll see you again in 25 years” at the end of Twin Peaks season two paying off in extraordinary fashion.

Laura Palmer’s body wrapped in plastic has become an iconic image both in terms of Twin Peaks and wider episodic television, inspiring numerous homages. Crucially, the series continued to build Laura’s story as the narrative progressed and aside from the stranger, otherworldly elements, the show continued to highlight the impact of her death on the entire community. Laura’s image hangs like a spectre across the opening credits of Twin Peaks, a powerful reminder of a life lost too soon, literally looming over the town. A tie-in book (The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer) penned by Jennifer Lynch and the 1992 film Fire Walk With Me, sought to expand upon the duality of Laura’s life and the tragedy surrounding her. Basing a television show around the premise of finding a girl’s killer could easily fall into being reductive, but instead the show made Laura the continued focus. Indeed, ‘Who killed Laura Palmer?’ is the driving force of the series, but it never forgets about her personhood. Special Agent Dale Cooper’s (Kyle McLachlan) desperation to solve her murder, leads to his capture in the Black Lodge and by the time of The Return also sees him try to retrospectively save her on the night of her death, eventually meeting with another double in the form of Carrie Page (also Lee).

That a young girl with a tragic history is given so much time, thought and impact in a series about her death makes Twin Peaks a truly special creation. While a thorough explanation for all the events contained within it feels impossible to truly pin down, the impact of Laura Palmer and in turn, Sheryl Lee in the enduring power of the show cannot be overstated.

Maureen Prescott - Scream

Maureen (originally Roberts) Prescott is an underseen but vastly important character within the entire franchise. Lynn McRee provides the face for the name in publicity shots, but as Maureen has died before the start of the franchise, she remains a memory. In Scream, her murder is referenced repeatedly, as is Sidney’s (Neve Campbell) erroneous belief that Cotton Weary (Liev Schreiber) is the man responsible for the crime. Gale Weathers (Courteney Cox) repeatedly antagonises Sidney about her refusal to look at other options, using her book and media platform to regularly bring the murder back to the surface. Maureen’s murder, much like that of Laura Palmer’s, casts a shadow over Woodsboro and the people within it.

Almost every killer across the Scream franchise is connected to Maureen in some way and many revelations are designed to shake Sidney’s confidence and happy, loving memories of her mother. That she had a secret and deeply traumatic Hollywood history that is explored within Scream 3 and which provides a new context to the events surrounding her death. In the first film, it is revealed that Maureen’s murder was as a result of her promiscuity - making her Billy’s target as he vents a particularly Oedipal brand of rage for the breakup of his parent’s marriage and the absence of his own mother. For both Sidney and Billy, the loss of that maternal figure sets their paths in life in very different ways. That her perceived promiscuity can later be read as a trauma response casts a whole new light on her life and death in a deeply sad way. Scream 3 utilises Maureen’s image and voice in a more overt way, rather than just in relation to Sidney, including a spoof of her voice.

The theme of fame (and the danger it comes with) repeats throughout the Scream franchise, with Sidney adapting to her trauma by alternatively denying and embracing the notoriety. Maureen is ultimately punished for seeking fame after facing the horrors of a sordid Hollywood underbelly, her abandoned son Roman (Scott Foley) seeks to punish Sidney for the attention she gains as a result and lastly, Jill Roberts completes the circuit, trying to create her own mythology to capture that infamy. To be known as a woman is to be placed in danger, a sobering theme in an otherwise often gleefully irreverent slasher skewering franchise.

Liz Purr – Jawbreaker

While the criminally underrated Jawbreaker may not sit comfortably within the genre, I would argue that this dark comedy invokes enough key elements to be considered a horror film. Focused on the aftermath of a birthday prank-gone-wrong where popular teenager Liz Purr (Charlotte Ayanna) is killed by a jawbreaker, the film takes an irreverent look at high school politics at their most extreme. Like Maureen Prescott, we hear relatively little from Liz Purr, aside from her shouts of “what are you doing to me” recorded on a birthday card as part of her initially good-natured, if incredibly misguided kidnapping. Courtney (Rose McGowan), Julie (Rebecca Gayheart) and Marcie (Julie Benz) are responsible for the death but have wildly differing responses. We see Liz mostly through the eyes of others, either in the form of her dead body as the trio try to carry her back to her room and pose her, or through dreamlike sequences.

What is particularly interesting about Jawbreaker is how it delves into the ways in which we view the deaths of women, particularly the young and beautiful. As part of their scheme to get away with her murder, Courtney (termed ‘Satan In Heels’ for good reason) concocts a story that feels close to that of Laura Palmer – a teenager with a dark side, engaging in sex acts with unknown men in bars. As Courtney sums up, “They'll believe it because it's their worst nightmare: Elizabeth Purr, the very picture of teenage perfection, obliterated by perversion”. As the girls stage their scene, which is constructed based on lurid headlines, they are caught in the act by dowdy Fern Mayo (Judy Greer). In a bid for Fern’s silence, they transform her into Vylette, a beautiful, fashionable exchange student. In this sense, Jawbreaker presents more than one missing woman as Fern loses herself to the bitchy glamour, while Julie becomes more disillusioned with Courtney’s casual cruelty.

Fern, however, is still present on some levels and a notable scene involves her detailing to Detective Vera Cruz (Pam Grier) how she would stare at the back of Liz’s neck during classes, making shapes out of the freckles on her neck. This imagined intimacy with Liz without her knowledge speaks to how her image is crafted as perfect. While Liz’s beauty is often highlighted, she is far from ornamental with the school genuinely thrown into grief from her loss as the far kinder counterpoint to Courtney.

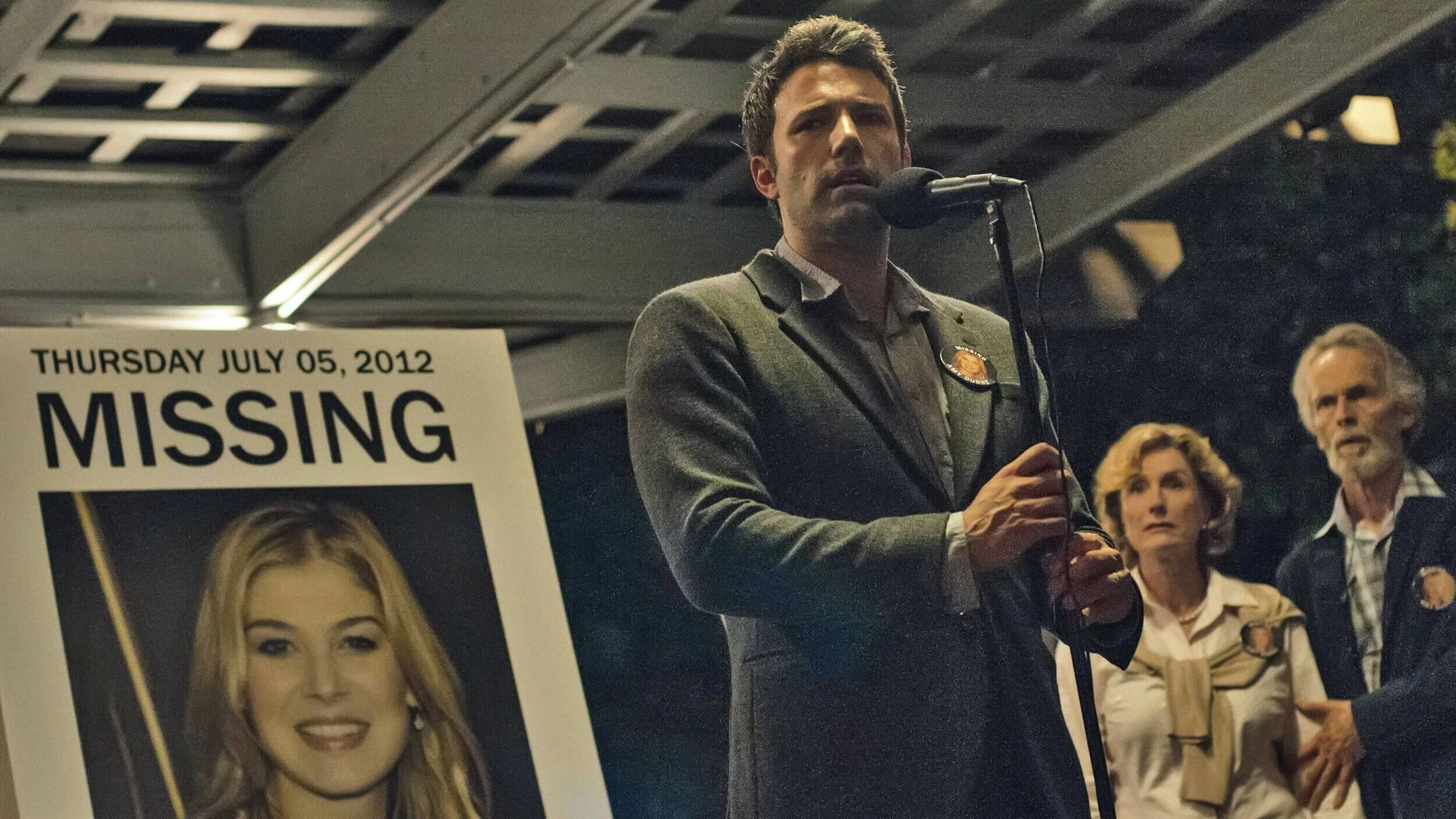

Amy Dunne – Gone Girl

So far, all the women within this article have disappeared or been murdered through no fault of their own, they are victims of either male violence or savage high school politics. Amy Dunne (Rosamund Pike) bucks the trend by choosing to leave her husband Nick (Ben Affleck) in the most explosive way possible in the slick thriller based on Gillian Flynn’s novel. While Jawbreaker investigates the construction and deconstruction of the tragic female figure, Gone Girl takes this a stage further, handing the pen to the woman herself. Amy has spent her life in the shadow of Amazing Amy, a book series about a virtuoso girl who excels at everything she turns her hand to (usually things real Amy has tried and given up on as an assumed passive aggressive strike), but proves to be skilled when she invents her own disappearance.

The theatre of the missing woman is on full display here and frequently the developments within the film feel uncomfortably close to real-life events such as the Laci Peterson case. Cameras, reporters and news networks descend upon Amy and Nick’s home as her disappearance becomes of national interest. Nick is thrown under intense scrutiny and into situations that there seems to be no right answer for – an ill-timed smile at a press conference or accepting casseroles from women he doesn’t know, positions him as suspicious even before the reveal of a younger girlfriend. Amy’s parents typically invoke the image of their very own Amazing Amy in their pleas for her safe return. Meanwhile, Amy has torn up her own social construct, dying her hair and allowing herself the foods she denied herself in her attempt to remain the ‘Cool Girl’. Amy’s Cool Girl monologue is a seething critique of the changes that women make for men and much of her anger at Nick is based on how he has allowed them to slip into traditional gender roles – she is a lonely, superficial nag and he is a dim bulb who prefers the simple things in life.

Of course, Amy, no matter how smart, is still trying to navigate a world which is hostile and after an attack in her hiding place she is forced to turn to Desi Collings (Neil Patrick Harris), who views her as ‘the one who got away’. What Amy does to remove herself from this situation is extreme, although her sociopathy and ability to transgress any kind of normal behaviour is no surprise by that stage. While Nick struggles to clear his name, Amy invents a new narrative for them, again breaking the (usually tragic) trend by returning, covered in blood and ready to resume her marriage. It is a subversion that is nowhere near heroic, but the calculated turning of how women are perceived into an advantage makes Amy a fascinating figure.

Abby – After Midnight

I wanted to end on a lighter, if still emotionally impactful note and Abby (Brea Grant) from Jeremy Gardner and Christian Stella’s After Midnight felt like the best possible option. After Midnight sees Hank (Jeremy Gardner) failing to come to terms with long-term girlfriend Abby’s departure. After she leaves, Hank’s devastation appears to manifest as a monster that visits the house nightly and scratches at the doors. The night-time visits drive Hank to increasingly extreme behaviour, becoming more disconnected from friends and work. Early flashback scenes focus the camera on Abby, to the point of cutting Hank out of frame to focus on her. Their relationship appears to be a happy one, and as the film cuts from flashbacks to the spaces now occupied by a lonely Hank, there is little sense of why she has gone. Certainly, local police officer and Abby’s brother Shane (Justin Benson) focuses his attention on Hank’s behaviour rather than mounting any search, although Hank’s insistence that something is in the woods hints at a possible tragic ending for Abby. Wade (Henry Zebrowski) is on hand to help Hank deal with his situation, but there is always the sense that Hank is the only one unaware of what has happened to Abby.

As the film progresses, the cracks begin to show in relatively subtle ways, from the fact that they were together for so long seemingly without any intent to marry, that Abby has a more sophisticated palette and from Hank’s drunken gazing at Jade (Taylor Zaudtke) who works at the bar that he and Abby manage. While nothing happens between the pair, there is a sense that the camera’s focus on Abby above all else at the start is an overcompensation for Hank’s wandering eye. After a particularly eventful night with the monster, Abby returns to the house. Again, the camera does a huge amount here – previously we have seen them in frame together but now they are in direct opposition and Abby no longer feels like a revered figure. She has the agency to go explore the life she thinks she wants and rather than remaining missing, she returns to confront her previous life with a renewed confidence and desire to make things work if at all possible.

This is until one of the film’s most incredible achievements: a long take featuring the pair having an honest conversation about their relationship failings while the camera zooms in almost imperceptibly. It is the first time we see them both in the same frame on the same terms and provides a turning point for seeing Abby not as a perfect girlfriend, but a living, breathing woman with more complex needs and desires than hinted at before. Acting as an awakening for both the audience and Hank, this scene is played perfectly and sets up for a later, incredibly emotional and romantic scene in which the pair appear to finally have it figured out. The camera again leads us to view them both from opposite ends of the table, but the performances and chemistry connect in a way that appears to secure their future as equals, rather than the earlier, more romanticised version that Hank tries to sell. I will not go any further into how it ends for them, as really, everyone should just go watch it and allow this incredible film to wash over them.

So, there you have it, five missing screen women that had an impact on their lives, family, friends, communities and entire franchises. Who are your favourites?

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Event Review] Highlights from Mayhem Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697624582491-MPT2VB9RRGU6OG7L6UKL/Mayhem+2023.jpg)

![[Editorial] Keeping Odd Hours: A Retrospective on Near Dark (1987)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445070868-HU9YIL3QPBCL1GW47R3Z/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.36.53.png)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] Soho Horror Film Festival: Interview with Aimee Kuge on Cannibal Mukbang](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1701808004722-9M8SZ2UXY52QBQBR4NTI/img20230818_15150780.JPG)

![[Editorial] Mayhem Festival: Interview with Thomas Sainsbury on Loop Track (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186472899-WC4RR0TW7L7LMFEBGPA2/Tom+Sainsbury.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Film Review] Kill Your Lover (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697465940337-T55VQJWAN4CHHJMXLK32/56_PAIGE_GILMOUR_DAKOTA_HALLWAY_CONFRONTATION.png)

![[Book Review] Wylding Hall (2015)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695484930026-PFRK7O26SLME4JIC49EW/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.59.04.png)

![[Film Review] Sympathy for the Devil (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186986143-QDVLQZH6517LLST682T8/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+09.48.52.png)

![[Film Review] Shaky Shivers (2022)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696442594997-XMJSOKZ9G63TBO8QW47O/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+18.59.33.png)

![[Film Review] V/H/S/85 (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697455043249-K64FG0QFAFVOMFHFSECM/MV5BMDVkYmNlNDMtNGQwMS00OThjLTlhZjctZWQ5MzFkZWQxNjY3XkEyXkFqcGdeQXVyMTUzMTg2ODkz._V1_.jpg)

![[Book Review] The Book of Queer Saints Volume II (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697187383073-U78VOF5WVDHI9YE8M98A/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+09.52.31.png)

![[Film Review] Elevator Game (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696440997551-MEV0YZSC7A7GW4UXM5FT/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+18.31.42.png)

![[Event Review] Saw the Musical: The Unauthorized Parody (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697187791989-OYMGLZO193B7XEMTJYGR/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+10.01.44.png)