[Editorial] Fearing Love, Loving Fear: How Horror and My Valentine Helped Me Reclaim My Story

I’ve always been a naturally anxious and markedly sensitive person. As a child, I spent most of my time split between attending school and traveling to the hospital for surgeries and therapy to learn things most able-bodied people don’t give a conscious thought to. 27 years and nine surgeries later, I still deal with near-crippling bouts of medical anxiety, not to mention anxiety of the social and just general brain-stuck-in-catastrophizing-mode variety. Years of being gawked at and laughed at for something entirely out of your control will do that to a person, though there were enough good people around to keep me going even when I wasn’t sure I could. I was usually a target for whispers and laughter behind my back because of a mix between the way my body moves and the fact that, generally, I don’t talk that much, and silence makes most people uncomfortable. I grew up in a small enough town that every kid ended up dumped into one high school even if they branched out in earlier years, which means for the most part I wasn’t out from under the scrutinizing eyes of my peers until I moved away for college. Anyone who tells you they miss their high school years probably peaked then while the rest of us were waiting to claw our way out of the masses.

Naturally, because most of the work for teaching kids not to be assholes to people who are different in school seems to fall primarily in the hands of the affected party, the ones I could not shift over to my side—the ones who did not spend any time getting to know me beyond their idea of me—added a healthy dose of fuel to my already tense and fluctuating perception of my body to create a pretty volatile mental space. If you’re outwardly different enough, nobody ever lets you forget it, not even yourself. No one was ever harder on me than I was, but I always knew when they laughed or expressed their disgust at the idea of relationships with me. As a result, I kept a lot of my feelings about myself and others bottled up inside and would often be criticized for being “too sensitive” and crying at even the slightest of my brother’s provocations at home. Sounds like the perfect recipe for a horror fan, no?

While in retrospect I can trace the evolution of my love for the genre pretty well along the path of my own acceptance of the things about myself I struggle with the most, for the first 16 years of my life horror films repelled me. I could read Edgar Allan Poe and the darkest fairy tale shit you could imagine and come away completely unfazed, and watched shows like Scooby-Doo and Courage the Cowardly Dog without batting an eye, but I avoided eye contact with the horror VHSs and DVDs in any given store as if looking at them would strike me dead, and it became a kind of joke in some parts of my family that I would fold myself into the smallest possible corners of a Party City at Halloween, stricken with terror at the sight of the wall of masks or the animatronics that moved when you walked past them. For all that, my mom tried her best to get me to watch some with her. She had grown up on horror and wanted to share it with me, but I was too much of a snotty pre-teen with preconceived ideas and unshakeable fears so that when she did manage to get me on the couch with her for a movie, I usually spent most of the time hiding behind a pillow or my phone, doing everything I could not to look at the events on the screen.

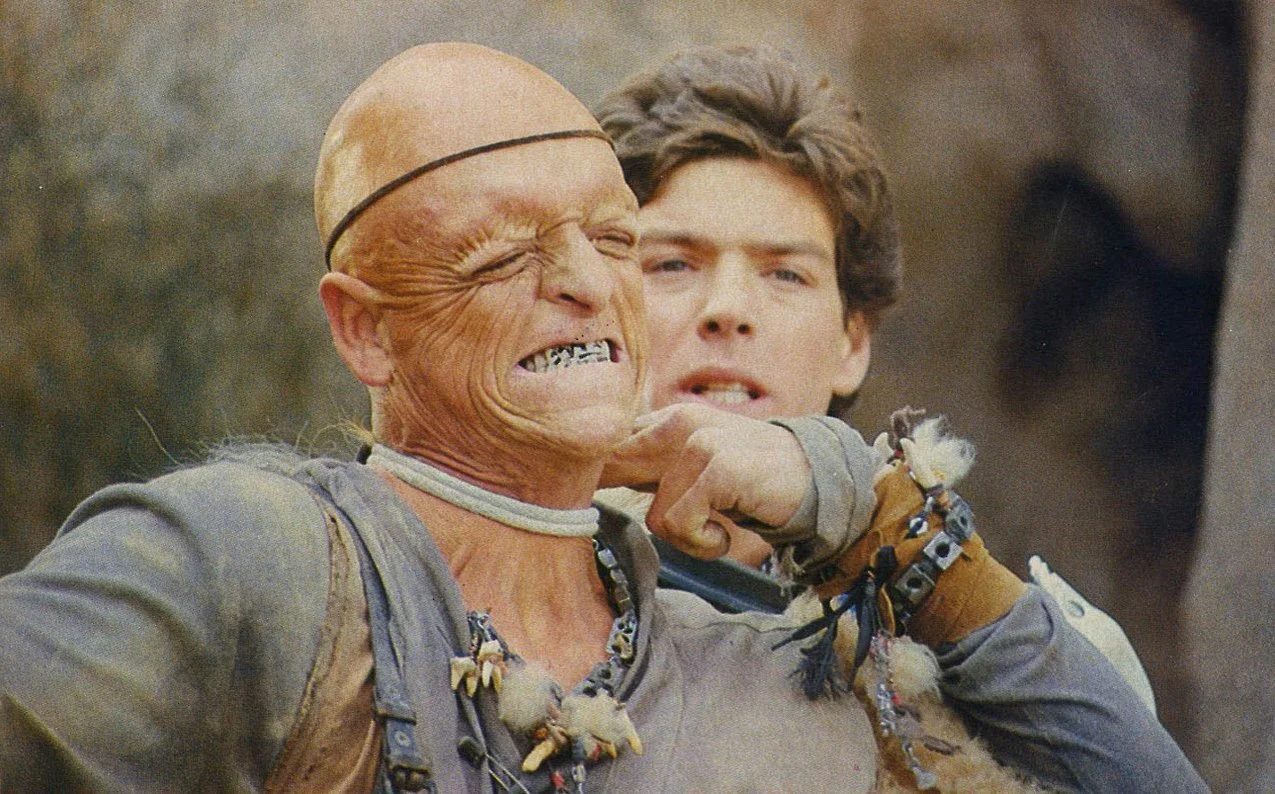

Then, one day, at a sleepover right around the time certain areas of my personal life were crumbling beneath me and no one I told seemed shocked or particularly comforting, I was tossed into a horror movie marathon with no escape route. My friend didn’t have a pillow for me to hide behind and she sat on my legs so that I could not leave the room. It was immersion therapy by way of Wes Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes, and it was like a switch flipped in my brain. I was—and am—still scared of what played out, but it was a controlled fear. I was in suburbia, after all, not wandering a Nevada desert with some cannibal family lying in wait. I hadn’t quite ever felt that level of control over my anxiety before; at least, not without a lot of focused breathing. Where my medical, social, and general anxieties would often flare up beyond my grasp to the point of making me shut down and feel sick, horror movies all but demand a communal experience of fear as verbal outcry and, with nowhere else to go, I was finally in the deep end. Horror movies most often operate in extremes and really watching them for the first time the way I did felt like a strangely appropriate counterbalance. The only way I would face my fear of them was when placed under extreme pressure, and so extreme pressure is what I was given; I sit here on the other end of it, grateful- if not constantly baffled.

I’m still probing the reason behind why I have grown to so passionately engage in a genre that I used to dismiss with equal venom. I am, as I said, no less afraid of them now than I was 10 or 12 years ago, yet the more I dig into the question the more I find that, for me, it became an environment not only to let my already anxious brain’s most extreme scenarios play out to a conclusion, but also to interrogate my constantly fluctuating relationship with my disabled body. At the most basic level, I have been rebuilt from the waist down. I walk with a gait that is distinct to people with CP but which to me feels more or less like a limp. I have balance issues and need help doing things and going distances most people don’t bat an eye at. I have grown to accept, on most days, everything this entails. But I have also discovered, much to my surprise, that horror films are the only genre that let people like me exist without the need to be miraculously cured. Yes, yes, the genre still has a ton of work to do, but lately it has been doing it. Where most other genres make people like me an object of either scorn or sympathy, horror is beginning to let us be the hero just as we are. Besides, it’s the only space where I can watch and imagine scenarios that put bodies like mine into, and increasingly frequently carve a space out of, danger. I’m already catastrophizing. Here, at least, I can strategize, too.

The more comfortable and occasionally confident I get with my disabled body, the more horror seems to be serving me in different areas of my life. As of late it has been doing a lot of heavy lifting for my mental health, especially through revenge films. I first noticed its impact while recovering from a particularly insidious abusive relationship. I had broken it off several months before but still had nightmares any time my ex tried to reach out to me and could still hear some of the more damning things they said to and about me echoing unbidden in my head. Then I found, through a friend who has no idea the kind of impact it had on me, Maggie Levin’s My Valentine, part of 2019’s Into the Dark series from Hulu.

Recommended as an entry to fill out a “movies you may have missed” list for that year, My Valentine was the story I didn’t know I needed. It follows Valentine (Britt Baron), a pop star recovering from an abusive and codependent relationship with her former boyfriend/manager. He has stolen her art and her public persona and molded it onto his latest girlfriend, leaving Valentine in a sad and desolate search for herself amid the wreckage. When she confronts him and his new girlfriend in a bid to reclaim her identity, he uses the all too familiar manipulative language of abusers who would rather you feel responsible for their actions than take responsibility themselves. While I am by no stretch of the imagination a pop star, Valentine’s battle for her sanity and the truth of her situation felt similar enough to my own that by film’s end I was leaping off my couch in joyful tears. Revenge films are some of the touchier entries in the genre. Given horror’s fraught relationship with women and minorities in general, finding solace in a subgenre that focuses on women in dire situations can often seem counterproductive to someone on the outside looking in. Yet, for me at least, they are more often than not cathartic environments to witness not just a kind of justice that feels largely unattainable in the real world, but also an unflinching validity to some of my own experiences. This does not mean I want to watch an assault happen. In fact, done right it becomes entirely unnecessary to show the assault at all. What matters is the emotions. Having something like that happen to you, no matter what toxic mixture of assault it is, can leave you numb, depressed, and angry. You can struggle to trust even the most well-meaning people because you might get stuck in a sort of fight or flight mode that leaves you more prone to assume the worst than the best of people’s intentions.

I saw echoes of this in the parts of Valentine’s story that mirrored my own. I, too, had spent months—if not years—being made to feel responsible for someone else’s bad decisions and lack of drive. I, too, had been driving myself deeper and deeper into a depression that left me floundering for a hold on who I was and what I loved to do—things I had only recently gotten a hold of and never released so completely before. The force that managed to undo almost every ounce of positive work I had done on myself had also been introduced to me under the guise of an endearing, helpful, motivated person who, in reality, was nothing but manipulative and entitled. To see that kind of person conquered so completely in a time of my life where I was still wondering if I would ever be free of their influence felt like a weight lifted from the fractured parts of my being. It was possible to find yourself and rebuild your identity from the foundations, and Maggie Levin’s film was proof. My Valentine held a mirror up to my most damaged corners and showed me how to have the strength to piece them back together in spite of the person who ripped them to shreds. It gave me a kind of release I’m not sure I’d have found in any other place at a time when I was still trying to put words to everything I had allowed myself to sacrifice.

Horror can do a lot of things for a lot of people. It can challenge us, make us uncomfortable, and even make us laugh. And every once in a while, if we’re really lucky, a piece of it will come along and see us. Hear us. Heal us.

![[Editorial] Editor’s Note: Getting sticky, slimy & sexy with body horror](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689072388373-T4UTVPVEEOM8A2PQBXHY/Society-web.jpeg)

![[Editorial] 8 Short & Feature Horror Film Double Bills](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687770541477-2A8J2Q1DI95G8DYC1XLE/maxresdefault.jpeg)

![[Editorial] 8 Body Horror Short films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690838270920-HWA5RSA57QYXJ5Y8RT2X/Screenshot+2023-07-31+at+22.16.28.png)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Maniac (2012) with Zoë Rose Smith and Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696356006789-NYTG9N3IXCW9ZTIJPLX2/maniac.jpg)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Female-Focused Mind Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691247166903-S47IBEG7M69QXXGDCJBO/Image+5.jpg)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Female-Focused Body Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689081174887-XXNGKBISKLR0QR2HDPA7/download.jpeg)

![[Editorial] Eat Shit and Die: Watching The Human Centipede (2009) in Post-Roe America ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691245606758-4W9NZWE9VZPRV697KH5U/human_centipede_first_sequence.original.jpg)

![[Editorial] Deeper Cuts: 13 Non-Typical Slashers](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694951568990-C37K3Z3TZ5SZFIF7GCGY/Curtains-1983-Lesleh-Donaldson.jpg)

![[Editorial] 5 Slasher Short Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696358009946-N8MEV989O1PAHUYYMAWK/Screenshot+2023-10-03+at+19.33.19.png)

![[Editorial] If Looks Could Kill: Tom Savini’s Practical Effects in Maniac (1980)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694952175495-WTKWRE3TYDARDJCJBO9V/Screenshot+2023-09-17+at+12.57.55.png)

![[Editorial] Metal Heart: Body Dysmorphia As A Battle Ground In Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690190127461-X6NOJRAALKNRZY689B1K/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+10.08.27.png)

![[Editorial] “I control my life, not you!”: Living with Generalised Anxiety Disorder and the catharsis of the Final Destination franchise](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696444478023-O3UXJCSZ4STJOH61TKNG/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.30.37.png)

![[Editorial] Editor’s Note: Making a slash back into September](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694354202849-UZE538XIF4KW0KHCNTWS/MV5BMTk0NTk2Mzg1Ml5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwMDU2NTA4Nw%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] They’re Coming to Re-Invent You, Barbara! Night of the Living Dead 1968 vs Night of the Living Dead 1990](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1687199945212-BYWYXNBSH00C4V3UIOFQ/Screenshot+2023-06-19+at+19.05.59.png)

![[Editorial] 8 Mind Horror Short films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693504844681-VPU4QKVYC159AA81EPOW/Screenshot+2023-08-31+at+19.00.36.png)

![[Editorial] Cherish Your Life: Comfort in the SAW Franchise Throughout and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695487675334-MYPCPYYZQZDCT548N8DI/Sc6XRxgSqnMEq54CwqjBD5.jpg)

![[Editorial] Keeping Odd Hours: A Retrospective on Near Dark (1987)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445070868-HU9YIL3QPBCL1GW47R3Z/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.36.53.png)

![[Editorial] Mayhem Festival: Interview with Thomas Sainsbury on Loop Track (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186472899-WC4RR0TW7L7LMFEBGPA2/Tom+Sainsbury.jpg)

![[Editorial] Soho Horror Film Festival: Interview with Aimee Kuge on Cannibal Mukbang](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1701808004722-9M8SZ2UXY52QBQBR4NTI/img20230818_15150780.JPG)

![[Event Review] Highlights from Mayhem Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697624582491-MPT2VB9RRGU6OG7L6UKL/Mayhem+2023.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Editorial] The Art of Horror in Metal](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695486401299-E5H2JNNJT26HKN0CI7WC/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.20.28.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] What to Watch at This Year's Cine-Excess International Film Festival 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697213510960-REV43FEOZITBD2W8ZPEE/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.01.15.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

This June we’ve been looking at originals and their remakes—and whilst we don’t always agree with horror film remakes, some of them often bring a fresh perspective to the source material. For this episode, we are looking at the remake of one of the most controversial exploitation films, The Last House on the Left (2009).