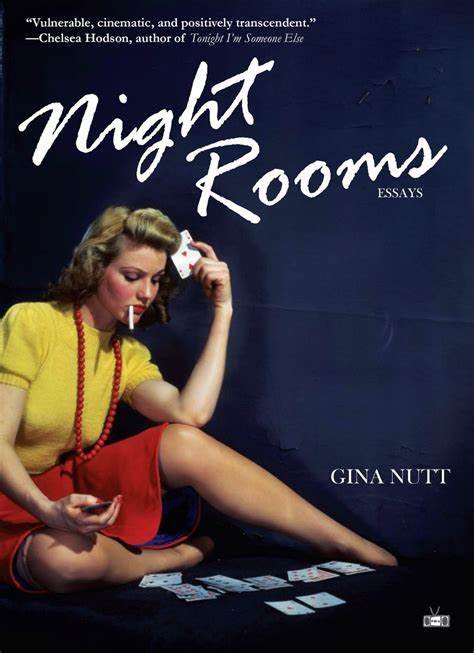

[Book Review] Night Rooms (2021)

In Gina Nutt's essay collection Night Rooms (2021), she artfully connects horror movies, horror books and the infamous "final girl" trope to events from her own life. She is a published poet, and her prose blooms as she vividly describes both what she's seen on screen and what she's seen in real life.

After a plumbing mishap (a modern-day horror if there ever was one), she says, "Hair-thin tree roots had grown through the pipes, feeding on the waste and water being carried from the house. The roots had backed water up into the washer as they thrived, thick as the thumbs of the men who came to cut up the sidewalk." While it's not what a horror fan typically thinks of when they hear "home invasion," the concept is there. Her house, her safe space, is invaded by mysterious outsiders that wreak havoc. Plumbing issues are banal, but Nutt imbues them with color and feeling. She brings the nightmare to life.

When Nutt was searching for a home, the experience was complicated by her vast knowledge of movies, TV shows and books about haunted houses. She discovers a website where one can pay for a report that lists the deaths that have occurred in a home. In the end, she doesn't buy the report, saying, "I tell myself I don't want to pay for the information. The truth is I'm too afraid to know."

Given her love for and encyclopedic knowledge of scary movies, one can hardly blame her for avoiding this disturbing information. Nutt calls horror movies "contained catastrophes," but if her own home were a place where deaths (especially violent deaths) occurred, the catastrophe is not at all contained; it would be a long-lasting nightmare. While she may appreciate haunted house films like Beetlejuice and Poltergeist, the possibility of a haunting in her own home isn't a can of worms she wants to open.

Nutt also mixes the story of a painful problem with her IUD, her memories of being a young ballerina, feelings of body dysmorphia and body horror, and moments from the classic giallo film Suspiria (as well as its 2018 remake). Has there ever been a more upsettingly perfect combination of female pain?

When Nutt's tattoo artist warns that her tattoo will stretch out when she has kids, she tells him that she doesn't want any. He informs Nutt, an adult woman, "Every girl says that." Later, Nutt chooses an IUD as her birth control method, but it shifts painfully inside of her. After the device is removed, she says, "I wanted another, even though I know it could happen again." In a world where women don't always have control over their lives (or increasingly, their own bodies), she knows she can at least control her chances of getting pregnant – she can control this particular body horror, even if it's painful.

A dance instructor implies that a young leotard-clad Nutt has a weight problem, telling her, "I can see your lunch." Nutt takes her own experience with this cruel teacher and swiftly connects it with the dancers from both Suspiria films. At the witch-run school, the dancers are often treated with contempt by their instructors, even as they push their bodies to the limit in the name of dance. Nutt describes a harrowing scene from the Suspiria remake: A ballerina "twists and bends until her bones break" when she is "beguiled by an unseen force."

The interdependent concepts of body horror and losing control over one's own body echo throughout Nutt's collection. As a teenager, Nutt self-harmed and experienced disordered eating, which culminated in a hospital stay. After confiding in a friend, rumors about Nutt spread, and she is bullied and threatened by her classmates. She thinks of Stephen King's titular Carrie, who also contends with the cruelty of her classmates. Carrie's feelings are so strong that she develops telekinesis with the onset of her first period. After a particularly devastating prank, she takes a very bloody revenge on her classmates.

Unlike Carrie, however, Nutt internalized her feelings (as many real-life teens do), trying to control what little she can by altering her body. She references Teeth and The Last House on the Left, which are both rape revenge stories, but ultimately, she says, "Revenge narratives often rely on someone harmed becoming as monstrous and violent as the person who harmed them. I am too soft to obliterate a tender self in favor of a cruel one." It's suggested in her essays that Nutt is a survivor of sexual assault, and as a result, her words here are particularly poignant.

The legacy of suicide also hangs heavy over Nutt in her Night Room essays. Many of her family members have died by suicide, including her great uncle, who was also a ballet performer. Nutt says, "At my most optimistic, minor research on family history is refused, a way to say, I won't." Even after experiencing depression herself, Nutt remains the final girl in her own story. She's faced tragedies, illness and violent deaths, but she comes out on the other side of it – and she lives to tell the tale. She notes:

"One assumption about a final girl being the person who lives to tell the story is that her survival is attached to telling; she is expected to say it, to tell, again and again; she can't live without a saying so revealing she is bare before the audience, the moment is bare."

By opening herself up in Night Rooms, Nutt is fulfilling part of the final girl trope. Every personal anecdote is another piece of her own movie; each story can be read as a tale of survival. She's the woman covered in blood who escapes at the end of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Nutt has battle scars – scars that she bravely exposes to her readers in this collection – but most importantly, she is alive. She has survived.

In the late seventies and early eighties, one man was considered the curator of all things gore in America. During the lovingly named splatter decade, Tom Savini worked on masterpieces of blood and viscera like Dawn of the Dead (1978), a film which gained the attention of hopeful director William Lustig, a man only known for making pornography before his step into horror.

On Saturday, 17th June 2023, I sat down with two friends to watch The Human Centipede (First Sequence) (2009) and The Human Centipede 2 (Full Sequence) (2012). I was nervous to be grossed out (I can’t really handle the idea of eating shit) but excited to cross these two films off my list.

Throughout September we were looking at slasher films, and therefore we decided to cover a slasher film that could be considered as an underrated gem in the horror genre. And the perfect film for this was Franck Khalfoun’s 2012 remake of MANIAC.

Many of the most effective horror films involve blurring the lines between waking life and a nightmare. When women in horror are emotionally and psychologically manipulated – whether by other people or more malicious supernatural forces – viewers are pulled into their inner worlds, often left with a chilling unease and the question of where reality ends and the horror begins.

When people think of horror films, slashers are often the first thing that comes to mind. The sub-genres also spawned a wealth of horror icons: Freddy, Jason, Michael, Chucky - characters so recognisable we’re on first name terms with them. In many ways the slasher distills the genre down to some of its fundamental parts - fear, violence and murder.

But some of the most terrifying horrors are those that take place entirely under the skin, where the mind is the location of the fear. Psychological horror has the power to unsettle by calling into question the basis of the self - one's own brain.

Body horror is one of the fundamental pillars of the horror genre and crops up in some form or another in a huge variety of works. There's straightforward gore - the inherent horror of seeing the body mutilated, and also more nuanced fears.

I can sometimes go months without having a panic attack. Unfortunately, this means that when they do happen, they often feel like they come out of nowhere. They can come on so fast and hard it’s like being hit by a bus, my breath escapes my body, and I can’t get it back.

Even though they are not to my personal liking, there is no denying that slasher films have been an important basis for the horror genre, and helped to build the foundations for other sub-genres throughout the years.

RELATED ARTICLES

Happily, her new anthology The Book of Queer Saints Volume II is being released this October. With this new collection, queer horror takes center stage.

It's fitting that Elizabeth Hand's novel Wylding Hall (2015) won the Shirley Jackson Award; her writing echoes and pays homage to the subtle scariness and psychological horror of Shirley Jackson's works.

Hear Us Scream Vol II is a collection of over thirty essays from horror writers, scholars and fanatics. Touching on topics ranging from the monster within, to family values and reclaiming our bodies through horror, this is a deeply personal collection. Every contribution is meticulously crafted and edited, with care and insight into the film and genre being discussed.

Gretchen Felker-Martin’s Manhunt, a novel that holds both horror and heart in equal regard, a biting and brilliant debut from one of horror-fiction’s most exciting names.

Penance is Eliza Clark’s eagerly awaited second novel following her debut Boy Parts, which found much love and notoriety in online reading circles.

Moïra Fowley’s debut adult work is a shapeshifting and arresting short story collection which looks at the queer female body through experiences both horrific and sensual.

A girl stands with her back to the viewer, quietly defiant in her youthful blue-and-white print dress, which blends in with a matching background

Nineteen Claws And A Black Bird packs in plenty of sublime and disturbing short stories across its collection.

However Nat Segaloff’s book The Exorcist Legacy: 50 Years of Fear is a surprising and fascinating literary documentation of the movie that caused moviegoers to faint and vomit in the aisles of the cinema.

Bora Chung’s bizarre and queasy short stories were nominated for the 2022 International Booker Prize and it’s no surprise why.

EXPLORE

The best thing about urban legends is the delicious thrill of the forbidden. Don’t say “Bloody Mary” in the mirror three times in a dark room unless you’re brave enough to summon her. Don’t flash your headlights at a car unless you want to have them drive you to your death.

Filmed on location in Scotland, Ryan Hendrick's new thriller Mercy Falls (2023) uses soaring views of the Scottish Highlands to show that the natural world can either provide shelter or be used as a demented playground for people to hurt each other.

If you know me at all, you know that I love, as many people do, the work of Nic Cage. Live by the Cage, die by the Cage. So, when the opportunity to review this came up, I jumped at it.

Perpetrator opens with a girl walking alone in the dark. Her hair is long and loose just begging to be yanked back and her bright clothes—a blood red coat, in fact—is a literal matador’s cape for anything that lies beyond the beam of her phone screen.

If you can’t count on your best friend to check your teeth and hands and stand vigil with you all night to make sure you don’t wolf out, who can you count on? And so begins our story on anything but an ordinary night in 1993…

A Wounded Fawn (Travis Stevens, 2022) celebrates both art history and female rage in this surreal take on the slasher genre.

When someone is in a toxic relationship, it can affect more than just their heart and mind. Their bodies can weaken or change due to the continued stress and unhappiness that comes from the toxicity.

When V/H/S first hit our screens in 2012, nobody could have foreseen that 11 years later we’d be on our sixth instalment (excluding the two spinoffs) of the series.

![[Editorial] If Looks Could Kill: Tom Savini’s Practical Effects in Maniac (1980)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694952175495-WTKWRE3TYDARDJCJBO9V/Screenshot+2023-09-17+at+12.57.55.png)

![[Editorial] Eat Shit and Die: Watching The Human Centipede (2009) in Post-Roe America ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691245606758-4W9NZWE9VZPRV697KH5U/human_centipede_first_sequence.original.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Maniac (2012) with Zoë Rose Smith and Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696356006789-NYTG9N3IXCW9ZTIJPLX2/maniac.jpg)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Female-Focused Mind Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691247166903-S47IBEG7M69QXXGDCJBO/Image+5.jpg)

![[Editorial] 5 Slasher Short Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696358009946-N8MEV989O1PAHUYYMAWK/Screenshot+2023-10-03+at+19.33.19.png)

![[Editorial] 8 Mind Horror Short films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693504844681-VPU4QKVYC159AA81EPOW/Screenshot+2023-08-31+at+19.00.36.png)

![[Editorial] 8 Body Horror Short films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690838270920-HWA5RSA57QYXJ5Y8RT2X/Screenshot+2023-07-31+at+22.16.28.png)

![[Editorial] “I control my life, not you!”: Living with Generalised Anxiety Disorder and the catharsis of the Final Destination franchise](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696444478023-O3UXJCSZ4STJOH61TKNG/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.30.37.png)

![[Editorial] Editor’s Note: Making a slash back into September](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694354202849-UZE538XIF4KW0KHCNTWS/MV5BMTk0NTk2Mzg1Ml5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwMDU2NTA4Nw%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Book Review] The Book of Queer Saints Volume II (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697187383073-U78VOF5WVDHI9YE8M98A/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+09.52.31.png)

![[Book Review] Wylding Hall (2015)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695484930026-PFRK7O26SLME4JIC49EW/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.59.04.png)

![[Book Review] Hear Us Scream Vol II](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1667055587557-4AIJTAG4N5VUZE8AC0SF/FrontCoverMarinaCollings.png)

![[Book Review] Manhunt (2022)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1683911513884-1Q1IGIU9O5X5BTLBXHV9/53329296._UY630_SR1200%2C630_.jpg)

![[Book Review] Penance (2023) by Eliza Clark](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695481011772-L4DNTNPSHLG2BQ69CZC1/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.54.07.png)

![[Book Review] Eyes Guts Throat Bones (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1682344253308-4AAFX12YD84EVJBYNJBZ/7e617654-8d9e-407e-8cde-33a97df84dcf.__CR0%2C0%2C970%2C600_PT0_SX970_V1___.jpg)

![[Book Review] The Aosawa Murders (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1678009096264-7QOOFO5PI9LAX47L3GF6/51054767.jpg)

![[Book Review] Nineteen Claws And A Black Bird (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1685872305328-UE9QXAELX0P9YLROCOJU/62919399._UY630_SR1200%2C630_.jpg)

![[Book Review] The Exorcist Legacy: 50 Years of Fear](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328003764-IASXC6UJB2B3JCDQUVGP/61q9oHE0ddL._AC_UF1000%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Book Review] Cursed Bunny (2017)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1680266256479-2E2XJT4T8CGAMOUB7XAL/298618053_5552736738082400_5168089788506882676_n.jpg)

![[Film Review] Elevator Game (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696440997551-MEV0YZSC7A7GW4UXM5FT/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+18.31.42.png)

![[Film Review] Mercy Falls (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695482997293-E97CW9IABZHT2CPWAJRP/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.27.27.png)

![[Film Review] Sympathy for the Devil (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697186986143-QDVLQZH6517LLST682T8/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+09.48.52.png)

![[Film Review] Perpetrator (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695483561785-VT1MZOMRR7Z1HJODF6H0/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.32.55.png)

![[Film Review] Shaky Shivers (2022)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696442594997-XMJSOKZ9G63TBO8QW47O/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+18.59.33.png)

![[Film Review] A Wounded Fawn (2022)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695484054446-7R9YKPA0L5ZBHJH4M8BL/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+16.42.24.png)

![[Film Review] Kill Your Lover (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697465940337-T55VQJWAN4CHHJMXLK32/56_PAIGE_GILMOUR_DAKOTA_HALLWAY_CONFRONTATION.png)

![[Film Review] V/H/S/85 (2023)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697455043249-K64FG0QFAFVOMFHFSECM/MV5BMDVkYmNlNDMtNGQwMS00OThjLTlhZjctZWQ5MzFkZWQxNjY3XkEyXkFqcGdeQXVyMTUzMTg2ODkz._V1_.jpg)

Looking for some different slasher film recommendations? Then look no fruther as Ariel Powers-Schaub has 13 non-typical slasher horror films for you to watch.