[Editorial] Room 237, Conspiracy Theories, and You

In July 64 A.D. a fire broke out in Rome. The fire began in a commercial neighborhood near the Circus where stores with flammable goods went up quickly. A particular gusty wind pushed the fire along through the Caeline and Palatine hills while citizens fled the city. Opportunistic looters and arsonists kept the blaze going for 6 days before it finally was put out. By the end, hundreds of people were either injured or killed. Only 4 of Rome’s 14 districts escaped any damage from the fire, including the emperor’s palace. In the aftermath, theories started to take hold.

One said Nero himself sent paid drunks to start the fire for his own entertainment. Another said Nero coordinated the burning to bypass the senate to rebuild the city as he saw fit. To counter, Nero blamed the fire on the unruly, upstart sect of Jews in the city who called themselves Christians and were quite unpopular with Roman citizens at the time.

The Conspiracy With a Thousand Faces

This is a conspiracy theory from nearly 2,000 years ago and it rings pretty familiar to the first big conspiracy theory of the 21st century--that the government somehow had a hand in the destruction of the World Trade Centers in New York City and the government’s counter narrative that a religious outgroup as a whole was to blame.

Conspiracy thinking has always been present, even the more culturally relevant conspiracy theories of today were around long ago, they simply wore a different face. The conspiracy about Nero and 9/11 are about the same thing: trying to make sense of a senseless event. Likewise, the conspiracy theories around vaccines and the possibility of a flat Earth are about the same thing: a distrust of modern science. University of Kent professor Karen Douglas researches and teaches social psychology and has found a common thread across conspiracy theories and the catalysts for their existence: the inherent need to resolve ambiguity, the social need to feel superior to other groups, and the lack of education or necessary intellectual tools to create informed theories.

So, at this point you may be asking, what does this have to do with horror?

Room 237

I’m willing to bet most of you reading this right now have not only seen The Shining, but seen it at least a dozen times. Perhaps you’ve paused it at all the spots the internet tells you to to look for clues or odd frames. Maybe you’ve mapped out the layout of The Overlook to prove the setting is geographically impossible. You’ve debated with friends as to whether the events were purely psychological or if that one thing we can’t explain necessitates supernatural aid. Stanley Kubrick’s perfectionist brushstrokes make it hard to ignore any single aspect of any single frame across his films. And that’s kind of the point.

Room 237 is a 2012 documentary directed by Rodney Ascher, produced by Tim Kirk and which invites a slew of talking heads (though they never appear physically on screen) to discuss their interpretations on The Shining. This ranges from Kubrick’s attempt to artfully talk about the Native American genocide to Kubrick’s confession via art that he helped fake the moon landing to theories about subliminal sexual messaging.

It’s an easy watch with friends over drinks and snacks. It’s easy to balk and laugh at some of the things shared by the participants in the documentary and their misguided earnestness. But, I’ve been thinking about Room 237 a lot lately as #1 podcasts and star athletes are given platforms to spout non-facts about public health and vaccines, as political factions continue to assert falsehoods on the national stage about the legitimacy of the current US administration. What is it that gets these people believing in this sort of thing? Truly believing and willing to march for it or go to jail for it.

And, like it can for most things in life, the answer can be found in horror.

Kubrick and the Esoteric

“It has always seemed to me that really artistic, truthful ambiguity – if we can use such a paradoxical phrase – is the most perfect form of expression. Nobody likes to be told anything,” Kubrick once said in an exclusive interview with Robert Emmett Ginna. In another interview with Vicente Molina Foix he said this about horror specifically: “About the only law that I think relates to the genre is that you should not try to explain, to find neat explanations for what happens, and that the object of the thing is to produce a sense of the uncanny.” Kubrick, and his adaptation of The Shining, is all about ambiguity and perspective. Which, as many of us know, is not at all what its source material is about.

The Shining, as written by Stephen King, is a pretty classic ghost story about a family battling domestic issues of alcoholism and abuse alone in a haunted hotel in the Colorado wilderness. The ghosts are real. Danny’s ability to “shine” (that is, clairvoyance of sorts) is real. And an abusive father and husband attempts to earn redemption. In Kubrick’s version, the hotel is not so obviously haunted as it is vast, winding, and unnerving in its isolation. The endless halls and echoes are their own ghosts and the Torrance’s bring their own demons of the mind that come out to play in the sprawling playground.

CRAVING EXCLUSIVE EXTRA CONTENT? CHECK THESE OUT!

One big question people love to discuss about The Shining is why Kubrick went so left field with his adaptation, one that Stephen King famously hates? As one of the many who has experienced both versions of the story and stared across the chasm between their themes, I too have asked why. But, in Room 237, the participants posit some answers. Each one more bizarre than the last.

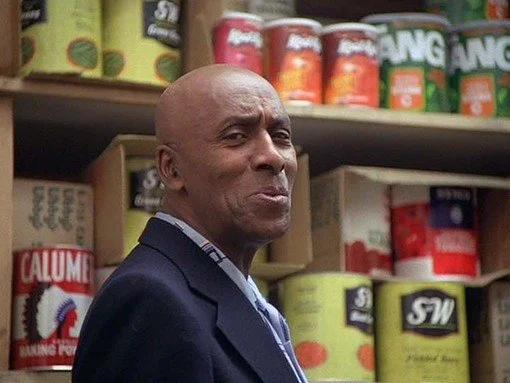

According to interviewee Bill Blakemore, the film is about the genocide of the Native Americans, revealed by the Calumet brand can of baking soda which features a prominent Native American in the logo. Calumet is the French word for a ceremonial smoking pipe used by certain Native tribes, which Blakemore refers to as a “peace-pipe”, and the symbolic presence of it in the film is representative of the peace treaties between the Native tribes and European colonizers. Later the Calumet cans appear again with the logo more obscured, leading Blakemore to suggest they represent broken treaties. Another: Kubrick, the “bored genius”, decided to make an entire film of subliminal techniques to tell an allegory of dangerous sexuality complete with implied phallic symbols. Or perhaps Kubrick’s film is a giant confession, as Jay Weidner suggests, that he helped NASA fake the footage of the moon landing. Or, as the German typewriter in several shots suggests, Kubrick’s trying to tell us the story of the Holocaust.

One thing particularly fascinating about The Shining is its place in the canon of Kubrick films, ranked by Kubrick fans. While horror fans love it, the film buffs aren’t so interested. One critic called it “Robert Corman on Robitusun”, that Kubrick had gone “terminally corny”. But, “we’re talking about a guy with a 200 IQ” so it had to be on purpose right? He had to be saying something.

One of Us

Without giving them the benefit of merit or details, I’ll say quickly we all know that conspiracy theories tend to fixate on one specific group. And, looking back at the example at the beginning, other marginalized groups also become easy targets. This is part of a two-pronged social need conspiracists have: the need to be a part of a special group and the need to punch down on any other group they see as a threat. This manifests both by blaming other ethnic, religious, or social groups and by affirming the conspiracist’s place as one of the select few paying attention, you sheeple. QAnon, in particular, really thrives on both these points of making horrifically racist memes about their perceived social enemies and sharing the keys to coded information that only they have the tools to decipher.

Thankfully, our Kubrick scholars are not so hateful, but they do make sure we know they understand things we don’t. The academic world of film study, for anyone who has even brushed tangentially against it, is competitive and runs on egos. I mean, how many times have you shared your opinion on a film only to have that one friend turn up their nose and pull out some French film terminology and talk about auteur theory? More casually, how many times have you been told your take is “wrong” about a film on Twitter? Interviewee Geoffrey Cocks makes note of his specific academic expertise as a German historian for his ability to crack the subtext about the Holocaust. Bill Blakemore credits his upbringing in Chicago along the Calumet River and summers hunting for arrowheads for why he alone seemed to grasp the reading regarding Native American genocide. And so on it goes.

Film study and film criticism is often a competition for who can prove they’re the smartest in the room and the work of Stanley Kubrick is the first-place trophy everyone in this documentary is gunning for. Each one of them brings a specialty in Kubrick’s work and insists on the definitive reading of the film along with their unique relationship with Kubrick as a filmmaker (Jay Weidner says at one point he owes Kubrick a debt for “everything I have become in my life”). Each one claims to understand the clues he left for them and only them. “How come I saw this,” Blakemore says of his interpretation, “and a lot of other people didn’t?”

“You’d have to be a complete fanatic like I am to find all this.”

Not Thinking Straight

Most conspiracy theories can trace themselves back to a simple misunderstanding of something. For example, we have plenty of explainable science for why the Earth is not flat, why climate change is real, why vaccines are effective and safe. But science is not always good at explaining itself to those of us without PhDs and some people take that a little personally. The defensive strategy is to call doctors quacks when they explain something you don’t understand, to point out how scientists once thought the Earth was the center of the galaxy when they talk about their latest working theories, to point out how many people are still getting sick despite vaccination.

This isn’t necessarily their own fault. The rise of the 24-hour news cycle and assertion journalism has put all sorts of nonfactual statements and unscientific theories right alongside actual science and facts. You can pretty much read stories about politicians eating babies right alongside the weather and your brain isn’t exactly wired to make an immediate context shift to understand the difference in merit. The Romans didn’t understand that blazes can create their own wind and fuel themselves just as most of us couldn’t really tell you the melting point of steel. But it sure is easy to read and understand statements like “Nero kept the fire going by not allowing efforts to put it out” or “the World Trade Centers were the target of an inside job because a plane couldn’t bring them down.”

Our Kubrick experts are all academics and/or writers and clearly well-educated and articulate. But that doesn’t mean they don’t have mental traps of their own. For many of them, confirmation bias is rampant in their analysis--all information that does not prove their point, or even outright contradicts it, is disregarded or weighted less against the evidence that does. We see this across virtually every single one of their arguments. Bill Blakemore’s fixation on the Calumet brand baking soda in the pantry ignores the dozens of other food brands also visible in both scenes he references (one of those brands in Tang, which might help Jay Weidner’s case about the moon landing theory). Geoffrey Cocks, as mentioned, is a German historian so he picks out the German brand typewriter alongside the number 42: “For a German historian, you put the number 42 and a German typewriter together and you get the Holocaust.” John Fell Ryan, who worked as a film archivist for several years and viewed dozens of reams of war footage he claims is fake dubbed “staged heroism” felt he was primed to spot a fake when he saw one and found “impossible” shots. When the claim comes up that Stanley Kubrick’s face is airbrushed into the sky in a moment only your subliminal mind can pick up, matrixing, or the brain’s tendency to force patterns out of chaos, does not come up as a possible solution. Ultimately, each of these people had unique perspectives and experiences they bring to their viewing. But that unique perspective doesn’t equate to truth, and the line between interpretation and definitive truth can be a dangerous one to cross. Our interviewers aren’t doing any harm by believing Kubrick is using subliminal advertising techniques or is trying to present an allegory for various genocides. But they are earnest in a way we should recognize, each one vehemently adamant about their interpretation, their view, their evidence, their feelings.

That’s the important thing here. I’m not equating reading The Shining as a new interpretation of the minotaur myth is anything close to some of the more despicable conspiracy theories out there today, but that’s what makes this film such an excellent tool for sifting through the noise. We all may look at the same headline or snippet of information and see dozens of different narratives from an objective truth. In a fire half of a city saw a conniving emperor while the emperor saw disloyal citizens. Either way, Rome burned.

And since I cannot possibly do justice to the chaotic universe in which the documentary exists, I encourage you to take a look for yourself. Look at the places where the arguments aren’t sound and why, or perhaps at the place where they unnervingly are and challenge the biases you bring to the story. What does that reveal about your own world, your own perception?

Don’t be afraid to explore.

![[Editorial] 8 Mind Horror Short films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693504844681-VPU4QKVYC159AA81EPOW/Screenshot+2023-08-31+at+19.00.36.png)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Female-Focused Body Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1689081174887-XXNGKBISKLR0QR2HDPA7/download.jpeg)

![[Editorial] 8 Body Horror Short films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690838270920-HWA5RSA57QYXJ5Y8RT2X/Screenshot+2023-07-31+at+22.16.28.png)

![[Editorial] Top 15 Female-Focused Mind Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691247166903-S47IBEG7M69QXXGDCJBO/Image+5.jpg)

![[Ghouls Podcast] Maniac (2012) with Zoë Rose Smith and Iona Smith](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696356006789-NYTG9N3IXCW9ZTIJPLX2/maniac.jpg)

![[Editorial] Editor’s Note: Making a slash back into September](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694354202849-UZE538XIF4KW0KHCNTWS/MV5BMTk0NTk2Mzg1Ml5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwMDU2NTA4Nw%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 5 Slasher Short Horror Films](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696358009946-N8MEV989O1PAHUYYMAWK/Screenshot+2023-10-03+at+19.33.19.png)

![[Editorial] If Looks Could Kill: Tom Savini’s Practical Effects in Maniac (1980)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694952175495-WTKWRE3TYDARDJCJBO9V/Screenshot+2023-09-17+at+12.57.55.png)

![[Editorial] Eat Shit and Die: Watching The Human Centipede (2009) in Post-Roe America ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691245606758-4W9NZWE9VZPRV697KH5U/human_centipede_first_sequence.original.jpg)

![[Editorial] Deeper Cuts: 13 Non-Typical Slashers](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1694951568990-C37K3Z3TZ5SZFIF7GCGY/Curtains-1983-Lesleh-Donaldson.jpg)

![[Editorial] Metal Heart: Body Dysmorphia As A Battle Ground In Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1690190127461-X6NOJRAALKNRZY689B1K/Screenshot+2023-07-24+at+10.08.27.png)

![[Editorial] “I control my life, not you!”: Living with Generalised Anxiety Disorder and the catharsis of the Final Destination franchise](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696444478023-O3UXJCSZ4STJOH61TKNG/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.30.37.png)

![[Editorial] The Babadook (2014)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1651937631847-KR77SQHST1EJO2729G7A/Image+1.jpg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Sara Lowes in Witchfinder General (1968)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1655655953171-8K41IZ1LXSR2YMKD7DW6/hilary-heath.jpeg)

![[Editorial] Margaret Robinson: Hammer’s Puppeteer](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1630075489815-33JJN9LSGGKSQ68IGJ9H/MV5BMjAxMDcwNDI2Nl5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwOTMxODgzMQ%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Tasya Vos in Possessor (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1667061747115-NTIJ7V5H2ULIEIF32GD0/Image+1+%285%29.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sara in Creep 2 (2017)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1646478850646-1LMY555QYGCM1GEXPZYM/27ebc013-d50a-4b5c-ad9c-8f8a9d07dc93.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sally Hardesty in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1637247162929-519YCRBQL6LWXXAS8293/the-texas-chainsaw-final-girl-1626988801.jpeg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Helen Lyle in Candyman (1992)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1649586854587-DSTKM28SSHB821NEY7AT/image1.jpg)

![[Editorial] American Psycho (2000)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1627317891364-H9UTOP2DCGREDKOO7BYY/american-psycho-bale-1170x585.jpg)

![[Editorial] Re-assessing The Exorcist: Religion, Abuse, and The Rise of the Feminist Mother.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1629995626135-T5K61DZVA1WN50K8ULID/image2.jpg)

![[Editorial] Lorraine Warren’s Clairvoyant Gift](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1648576580495-0O40265VK7RN03R515UO/Image+1+%281%29.jpg)

![[Editorial] Unravelling Mitzi Peirone’s Braid (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1628359114427-5V6LFNRNV6SD81PUDQJZ/4.jpg)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)