[Editorial] Shame, Fear, and Pain in The Poughkeepsie Tapes

*Trigger warning for emotional abuse and self-harm*

Something about The Poughkeepsie Tapes called to me. I knew it was an intensely disturbing Found Footage film and I’d heard friends speak about it in the same hushed tones reserved for A Serbian Film and Salo. I didn’t know anything more about the film, but it felt like a challenge, a way to prove how tough I was.

And of course, I wanted in on the secret. So, I watched it on a bright and sunny Saturday morning. While not what I expected, it is the most disturbing and upsetting film I’ve ever seen and, after the final credits, I sat in silence, staring at the wall for a while. I’m sure other films are technically more violent and of course I haven’t seen every movie, but something about The Poughkeepsie Tapes seemed to resonate with me. In the following days and weeks, my mind kept returning to it, replaying images, and turning scenes over and over in my brain

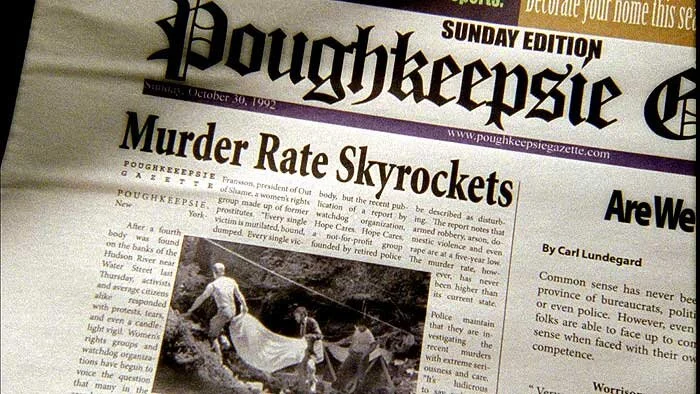

The titular tapes consist of hundreds of VHS home movies made by the so-called Water Street Butcher. While some contain fetish play, more show torture, rape, murder, and dismemberment. They are filled with depravity. Many show footage of Cheryl Dempsey, a young woman kidnapped by the Butcher and held prisoner for eight years before she is found by police along with the tapes. The faux documentary centers itself on both the Butcher and his primary victim, Cheryl, and it was in understanding her story that a crucial part of my own life suddenly came into focus. This essay is an attempt to process and explain that revelation.

It’s difficult to recommend this movie to anyone, it’s simply too disturbing and there is a valid argument that it fetishizes violence against women, however I do find value in The Poughkeepsie Tapes. It’s a harsh examination of the predatory male gaze and cinematic exploitation. We never learn the identity of the Butcher or even see his face. We experience his crimes through the gaze of his camera and the perspective of those suffering in the wake of his atrocities. This vague identification allows us to project our own tormentors onto his image: the killers, the abusers, the bullies, the patriarchy itself. But to me, the Water Street Butcher became a representation of my father.

I was raised by a narcissistic, emotionally abusive man. For eighteen years, I lived in fear, wondering what I would inadvertently do that day to make him mad and how harsh the punishment would be. He never physically hurt me, but the emotional abuse caused psychological wounds that I feel to this day. Three years into therapy, I’ve only cracked the surface of how this trauma has affected the way I see myself and the way I engage with the world. I know my dad loves me, or at least he thinks he does, but his love is conditional and must be earned by my behavior.

Because the rules for how to earn that love were always changing, I lived in constant fear that I would do something wrong. Even scarier was the thought that simply existing as my authentic self was the thing I had done wrong and I would never be good enough to earn consistent love and safety. My mother told me he was a perfectionist and so I believed that any time he was mad, it was because I wasn’t perfect. I became hypersensitive to his moods and emotions, trying to guess what would trigger his rage and what I should pretend to be in order to earn the parental love I craved. As a consequence, I learned to equate that love with fear, shame, and pain.

While the abuse Cheryl endures during the film is much more extreme, it follows similar patterns. In videos soon after her abduction, the Butcher commands her to repeat words and phrases, identifying herself as “Slave” and saying she’s glad he murdered her parents. When she resists, she is savagely beaten or attacked. Eventually she says what he wants her to say to make the torture stop. She begins to modify her behavior based on what she thinks will please him, even killing for him, terrified of the pain she knows is coming if she steps out of line. At one point, the Butcher makes Cheryl wear a rubber mask, erasing her essential self and replacing it with his ideal. He forces her to stare at herself wearing the mask in the mirror, internalyzing that Cheryl is gone, all that’s left is a slave.

Anytime she shows will of her own, he punishes her then reminds her that it was her action that triggered his anger and thus her fault. If she had just been good, he wouldn’t have had to hurt her. She begins to blame herself for her own torture, fully seeing the world through his lens because maintaining her own autonomy is too dangerous. She begins to believe that not only is Cheryl gone, but that he had to destroy her chosen identity because it wasn’t good enough to deserve his love. His torture is a way to make her perfect and if she can just maintain that perfection, the pain will stop.

After Cheryl is rescued, the hospital psychologist recounts noticing that her wounds are not healing and are in fact, getting worse. Through eight years of horrific torture, she learned to define her life through pain and without the Butcher to cause it, she began hurting herself. The psychologist says, “Pain had been such a huge part of her life for so long, she didn’t know how to exist without it.” This sentence unlocked something in my brain that I’d been struggling with for most of my life and, though triggering, helped me understand my own desire for pain and shame. I do not trust happiness. My brain tells me that feeling good is a sign that I have let my guard down and am likely to do something wrong. I am in danger because in allowing myself to feel good, I have forgotten to be perfect.

When I moved out of my parents’ house, I began dating men who were mean to me. Several of them were alcoholics and my first husband was physically abusive. I didn’t understand how to be in a relationship that didn’t hurt in some way and if the man I was with wouldn’t cause me pain, I would do it myself. Sometimes I would date a man who treated me well and as the relationship progressed, I tried to sabotage it. I pushed him away so that I could feel the fear that he would leave me, the pain of his anger, and the shame of his rejection. I told myself that I wanted to be happy, but that happiness felt too risky, a sign that I had become comfortable. I had internalized that I was not good enough for these men, because I was never good enough for my father, so if he liked me at all, it was because I was successful in being who he wanted me to be. I had found the right mask.

I even wanted sex to feel bad. I would ask men to either hurt me or restrain me because I had been conditioned to believe that all love, even the physical act, should cause some kind of pain. The only way I could really ask for this was with the help of alcohol and I would routinely drink so much that I would black out, making it easier to ask for what I had decided was a shameful desire to be humiliated. These binges were also a way of tapping into my self-destructive tendencies and while I dreaded the painful hangovers and morning-after inventory of my barely remembered behavior, I also felt like I deserved them. Feeling like shit was what I understood to be my natural state and anything more felt like pretending.

I eventually got sober and married a man who loves me unconditionally, but the need for pain did not go away. I find emotional intimacy extremely difficult and often push him away so that I can avoid the moment when he inevitably finds out how worthless I believe myself to be. It feels safer to put on the mask of what I think he wants rather than allow him to see who I really am because that vulnerability is terrifying.

I also began engaging in self-harm. When I’m feeling particularly fragile, I drag a thumbtack across the back of my forearm in what I think of as “scratching.” I rarely break the skin, but the longer the mark lasts, the more satisfying it is. I feel like I’ve paid for whatever it is my brain has told me I’ve done wrong and the cycle is complete. With no one around to punish me, I do it myself. Adding to the pain, I leave these marks in an easily visible part of my body, ensuring that the fear of someone discovering my secret is always present. For so long, pain was my natural state and though it hurts, leaning into that fear and shame at least feels familiar.

The Poughkeepsie Tapes concludes with an interview with Cheryl after her release from the hospital and the difference in the girl we’ve seen in home videos before her abduction and the woman who returns home is shocking. She feels uncomfortable when the interviewer won’t tell her what to say because for so long she lived with the terror of making that kind of choice for herself. When she does have thoughts of her own, they are in praise of “master.” As protection from his cruelty, she made herself believe that his torture was an expression of love and she’s desperate to get it back.

I was similarly brainwashed and believed for most of my life, that my father’s love was just his way of teaching me to be better. I still have a relationship with him, but it is strained. To get through our interactions, I must maintain that mask of perfection to avoid his anger. I watch Cheryl describe the Butcher and recognize the lies I told myself about my own family. I see her mangled body and wonder what I would look like if the emotional scars were visible on my own. What would be left of me? Would I recognize myself?

I’m writing this not to advocate for or defend any of my actions. I worry about spreading ideation and negatively affecting those who are vulnerable to the same kind of temptation. I go to a lot of therapy and I am trying to work through what feels like a jumble in my brain, but it takes time. When describing Cheryl’s torture, one of her doctors says that some of the trauma she suffered is too upsetting to be said out loud. While perhaps true, that leaves Cheryl alone in the knowledge of what she’s been through. Surely if she can endure it, we can endure talking about it.

Part of me wonders if the act of writing this essay is yet another way to cause myself pain. Is my ultimate goal to spark the cycle of humiliation and punishment by revealing secrets I’ve kept deeply hidden and exposing the pieces of my life I’ve been told to believe are shameful? But a larger part of me knows that there is power to be found in exposing our wounds to the light. Maybe someone else will recognize a piece of Cheryl’s story, or my own, and we can share an authentic connection. Maybe we can attempt to take off the masks we wear as protection and show our true faces to the world. Maybe that’s how we heal.

![[Editorial] Films To Ruin Your Day: Guinea Pig Series](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1654336384638-RERLWENSWVNSQKJSG0IZ/image5.png)

![[Editorial] Films To Ruin Your Day: So You Really Think You Have a Serial Killer Obsession?](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1619379312146-V464N7U6XUEU6F8EWLCS/the-poughkeepsie-tapes-featured.png)

![[Editorial] Films To Ruin Your Day: Vomiting & Genital Mutilation](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1611125437442-DTVQ8AZOLB516WDTPQS4/Martyrs-2008.jpg)

![[Editorial] Films To Ruin Your Day: Submission & Abuse](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1614454639368-ILL23SRCXB266EY0L44J/thebunnygameposter_zps5128dbb3.jpg)

![[Editorial] Films To Ruin Your Day: Getting Fucked To Death](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1611042150655-V2VS3BDIJ2JM85RSZCG4/Where+Dead+go.jpg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Tasya Vos in Possessor (2020)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1667061747115-NTIJ7V5H2ULIEIF32GD0/Image+1+%285%29.jpg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Helen Lyle in Candyman (1992)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1649586854587-DSTKM28SSHB821NEY7AT/image1.jpg)

![[Editorial] In Her Eyes: Sara Lowes in Witchfinder General (1968)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1655655953171-8K41IZ1LXSR2YMKD7DW6/hilary-heath.jpeg)

![[Editorial] Unravelling Mitzi Peirone’s Braid (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1628359114427-5V6LFNRNV6SD81PUDQJZ/4.jpg)

![[Editorial] Margaret Robinson: Hammer’s Puppeteer](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1630075489815-33JJN9LSGGKSQ68IGJ9H/MV5BMjAxMDcwNDI2Nl5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTcwOTMxODgzMQ%40%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] The Babadook (2014)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1651937631847-KR77SQHST1EJO2729G7A/Image+1.jpg)

![[Editorial] Lorraine Warren’s Clairvoyant Gift](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1648576580495-0O40265VK7RN03R515UO/Image+1+%281%29.jpg)

![[Editorial] Sally Hardesty in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1637247162929-519YCRBQL6LWXXAS8293/the-texas-chainsaw-final-girl-1626988801.jpeg)

![[Editorial] Sara in Creep 2 (2017)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1646478850646-1LMY555QYGCM1GEXPZYM/27ebc013-d50a-4b5c-ad9c-8f8a9d07dc93.jpg)

![[Editorial] American Psycho (2000)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1627317891364-H9UTOP2DCGREDKOO7BYY/american-psycho-bale-1170x585.jpg)

![[Editorial] Re-assessing The Exorcist: Religion, Abuse, and The Rise of the Feminist Mother.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1629995626135-T5K61DZVA1WN50K8ULID/image2.jpg)

![[Mother of Fears] I Don’t Wanna Be Buried in a Pet Sematary (1989) and (2019)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1691328766069-QFNAVJOMFZVZ5CLU1RWM/Screenshot+2023-08-06+at+14.23.13.png)

![[Editorial] 10 Films & Events to Catch at Soho Horror Film Fest 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1700819417135-299R7L4P0B676AD3RO1X/Screenshot+2023-11-24+at+09.41.52.png)

![[Editorial] 5 Female Focused Horror Book Recommendations](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696441981361-52EQCTJ7AT2QF1927GM7/919xtm6d3fL._AC_UF894%2C1000_QL80_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 Terrifying Cerebral Visions in Horror Movies](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1693509801235-X23OL50T1DVGECH0ZJK2/MV5BMjQ0MTg2MjQ4MV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTU3NDgxMTI%40._V1_.jpg)

![[Editorial] 9 Horror Nintendo Switch Games To Play](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1697214470057-3XZXX8N4LYIMDFWS6Z3P/Screenshot+2023-10-13+at+17.20.13.png)

![[Editorial] 9 Best Slashers Released Within 10 Years of Scream (1996)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695478839037-LOFHGVM3H6BMSZW7G83M/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+15.15.11.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mother Vs. Monster in Silent Hill (2006)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1695485781119-H6GNP0G3J2TLPAOIABV7/Screenshot+2023-09-23+at+17.11.56.png)

![[Mother of Fears] Mothering in Silence in A Quiet Place (2018)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fe76a518d20536a3fbd7246/1696445921315-HZJ2DZYQIH6VVWXBO2YL/Screenshot+2023-10-04+at+19.52.29.png)

During a week of movie viewing, I happened to stumble across a little pig fucking trend…